The Boring Chips That Brought Europe to Its Knees

Discrete diodes, transistors and ESD protection devices don't make headlines, but Nexperia's automotive components are now the center of a geopolitical standoff threatening European car production.

Welcome to a 🔒 subscriber-only deep-dive edition 🔒 of my weekly newsletter. Each week, I help investors, professionals and students stay up-to-date on complex topics, and navigate the semiconductor industry. If you’re new, start here. As a paid subscriber, you will get additional in-depth content. See here for all the benefits of upgrading your subscription tier!

This is a video essay talking through this post along with key highlights that you can quickly browse through, for paid subscribers only.

While the world was steeping in 100 billion dollar circular AI deals, the rug was pulled out from under the semiconductor industry last week by a single company that produced mundane but essential components for the automotive semiconductor market: Nexperia.

There is plenty of online coverage about what exactly happened. In this post, I will briefly explain what went down, why the automotive industry is a complex beast, and what the road ahead looks like for the European automotive industry.

For free subscribers:

The Dutch Takeover and End of Chinese Exports

Understanding Nexperia and Automotive Markets

The Automotive Qualification Barrier (AEC Standards)

For paid subscribers:

The Turning of Tables: What happens next, and who are viable replacements for Nexperia.

Read time: 10 mins

The Dutch Takeover and End of Chinese Exports

From Nexperia’s official release:

Due to the same serious managerial shortcomings, the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs observed that Nexperia’s operations in Europe were being compromised in an unacceptable manner. This situation raised broader concerns for the Dutch government about the availability of semiconductor products critical to the European industry.

The combination of Zhang Xuezheng’s behaviour as CEO and (indirect) shareholder, as well as concerns about the semiconductor product availability in the Netherlands and Europe, ultimately led to the Dutch government to intervene with an exceptional emergency order on the basis of the Goods Availability Act (Wbg).

The Goods Availability Act was enacted in 1952 for post-WWII reconstruction efforts and allows the Dutch government to control critical goods during national emergencies, and its application to Nexperia was the first time the law was ever used. The Dutch government was prompted to use this historically extreme measure because they believed that the actions of a Chinese entity would undermine their access to critical semiconductor chips. It comes down to two specific reasons: WingSkySemi and US export controls.

Investments into WingSkySemi

A Dutch court ruling contains specific allegations that the Zhang Xuezheng (’Wing’), the CEO of WingTech - an “obscure” Chinese company that purchased Nexperia from NXP in 2018 for $3.6 billion - used Nexperia’s money to finance chip manufacturer WingSkySemi, and attempted to fire European executives. Although some of Nexperia’s products are made in WingSkySemi, the chip factory ran into tough times in the past due to lack of sufficient orders. The ruling states that Wing used Nexperia funds to fill up the factory capacity by placing “scrap” orders that was ~3x more than Nexperia’s actual product needs. Wing has currently been suspended as Nexperia’s CEO.

US putting Nexperia into the Export Control list

In December 2024, the US Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) added Nexperia to its “Entity List” for export controls because it is wholly owned by Chinese company Wingtech. This directly affects Nexperia’s ability to manufacture electronics because the hardware and software tool chain often involves US-made components, which would become unavailable. The Dutch government feared that WingTech would relocate Nexperia’s assets to China in response to US export controls, effectively cutting them off from automotive chips. US export controls makes the whole dynamic of “designed in Europe, manufactured in China” unviable.

In retaliation to the Dutch takeover, China imposed export restrictions disallowing any Chinese made components from being exported to Europe - effectively cutting off European auto manufacturers from getting the parts they need to produce cars. This has led to auto makers like Volkswagen warning that their production line could completely stop if electronic parts were not available.

The Chip Letter has a nice historical take on Nexperia, if you want to understand the grander scheme of things. If parts from one supplier, Chinese or not, can bring a continent to its knees in the automotive sector, it is useful to understand the importance of Nexperia and the automotive industry itself to some extent.

Understanding Nexperia and Automotive Markets

In Nexperia’s own words, they supply “essential semiconductors” to a wide range of industries including cars, power tools, medical devices, and mobile phones. Their products are basic - like BJTs, diodes, ESD protection devices - but critical to the operation of a wide variety of electronic devices, especially in vehicles. These “everyday” parts go into power windows, lighting systems, safety features like airbags and ABS, and power converters. They mostly utilize mature process nodes that don’t appear in news cycles but the resulting products are essential to modern electronics in every way.

While their frontend wafer fab facilities are in Europe (Germany and UK), the packaging and assembly is entirely dominated by Southeast Asia (China, Malaysia, Philippines), with a majority of products (est. 70-80%) emerging from the assembly facility at Dongguan, China.

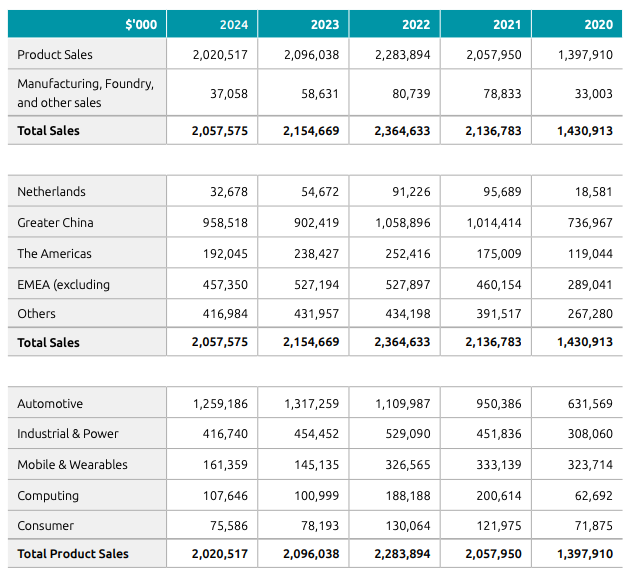

From their 2024 sustainability report, Nexperia is essentially a company with $2B in sales which is a far cry from today’s trillion dollar semiconductor giants. About 46% of their sales are within China, while EMEA accounts for 22%. Interestingly, the Americas only account for 10% of total sales; this supply chain crunch is a bigger deal for Europe than it is for America. About 60% of their revenue comes from the automotive sector, while industrial/power accounts for another 25%. These numbers convey a simple message: Nexperia is a critical automotive supplier in Chinese and European markets.

The whole news cycle around this company begs a simple question: Why don’t auto makers in Europe just source parts from some other company - especially if they are not cutting-edge technology - if Nexperia China is unwilling to ship them what they need? The answer lies in meeting stringent automotive qualification standards, and who is capable of doing so.

The Automotive Qualification Barrier (AEC Standards)

Switching suppliers in a matter of weeks is a difficult proposition in any semiconductor industry because agreements and inventory cycles are established months in advance to ramp up production to meet demand. Automotive standards and safety requirements take the difficulty level a notch higher.

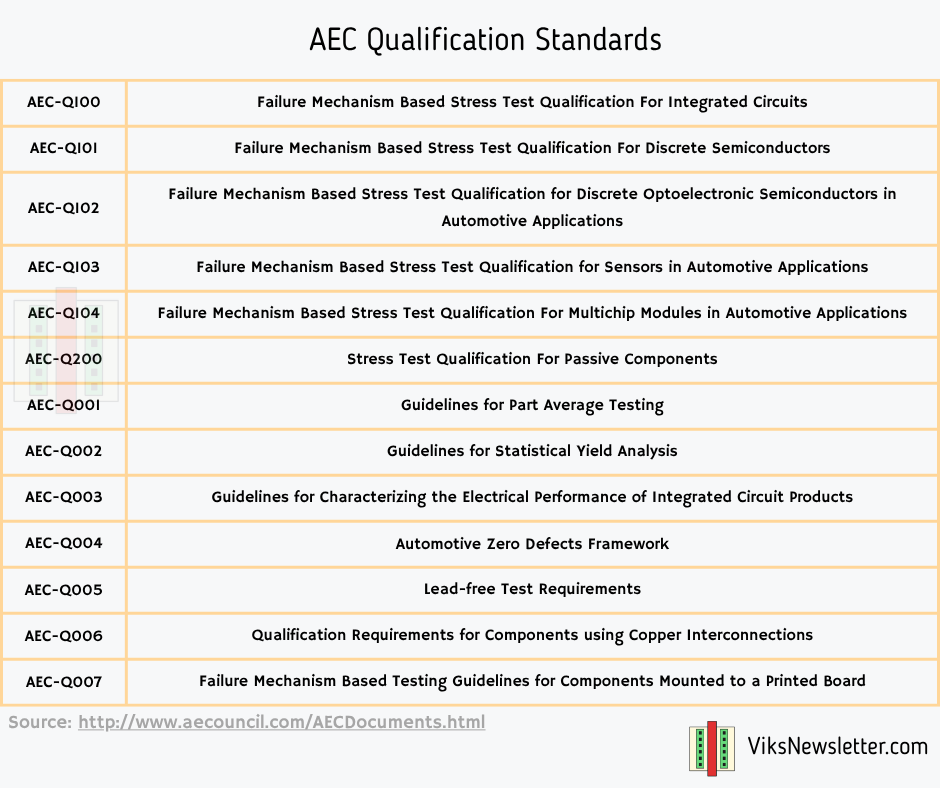

The Automotive Electronics Council (AEC) has standards that must be met for various kinds of electronic components used in vehicles. Active components involving transistors of any kind generally fall into the Q100 family of standards, while Q200 is for passive components. The detailed classification from AEC is as follows.

The difficulty of automotive qualification stems from two tough requirements:

Extreme temperature and lifetime requirements: Devices have to operate over a wide range of ambient operating temperatures and survive up to 15 years in harsh conditions of elevated temperatures, humidity, and environmental variations that push devices, materials and packaging to their limits.

“Zero-defect” reliability expectations: Parts designed for automotive use require design margins well beyond consumer-grade products because they have stringent reliability needs, often >99% with 90% confidence over a large sample of products, and diverse environmental conditions.

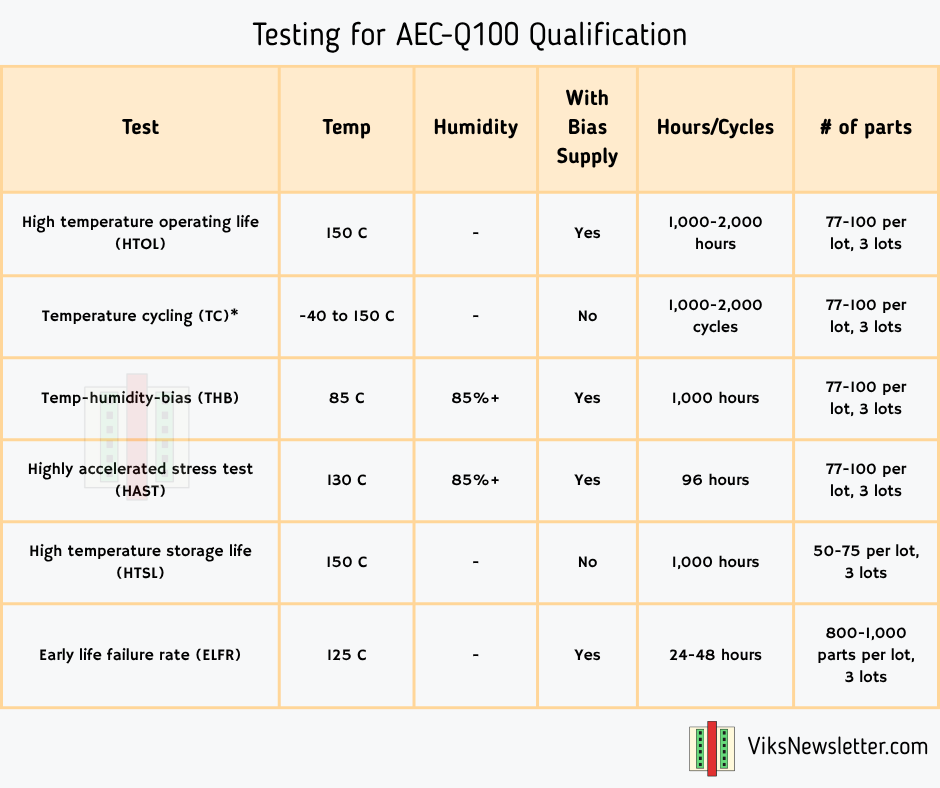

The table below shows the battery of tests, and the conditions involved in achieving automotive qualification. The numbers are representative, and can vary depending on the automotive grade being qualified for, and the testing requirements of the OEMs incorporating the parts in their designs. Tier 1 OEMs regularly demand double the testing times shown below.

The purpose of these tests is to evaluate the ruggedness of the automotive part in real life conditions. High temperature testing often accelerates the aging process and allows the evaluation of ruggedness within a few weeks. The accelerated testing results are then extrapolated to lifetime in years. This complete qualification process for a new part can easily take 3 months, assuming that tests pass criteria as planned.

Then there are tests related to electrostatic discharge (ESD) based on different discharge models called HBM (human body model) and CDM (charged-device model) where the part is zapped with hundreds or thousands of volts, and then tested again for performance changes. There is also a battery of tests related to mechanical sturdiness that involves pulling on wirebonds, testing them in vibration, drop and shock environments, and a whole lot more. Finally, qualification testing needs to be demonstrated over hundreds of parts per wafer lot, with at least three different lots.

AEC-QXXX qualification is among the most demanding qualifications in the electronics industry, and companies will only attempt this process if there is a clear automotive demand. The time, expense and personnel needed to perform the diverse battery of tests required needs solid justification.

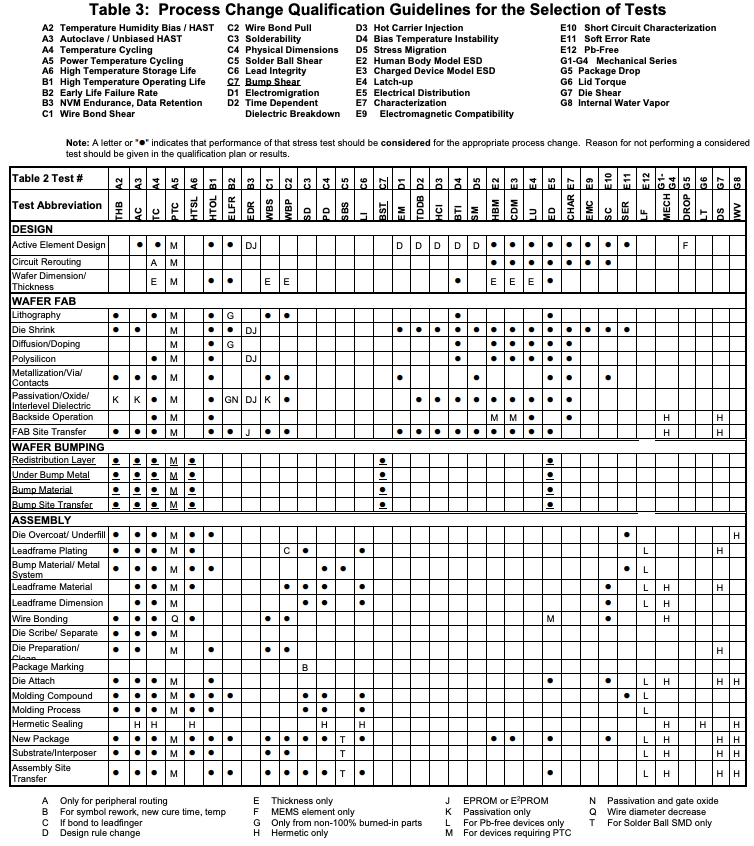

To be fair, a lot of commercial electronics is also regularly subject to many of the above lifetime and ESD tests; automotive electronics takes it much further due to the harsh environments they need to operate in. This mind-boggling chart below gives a glimpse of how complex automotive qualification is.

This gives a glimpse as to why auto makers are in a pickle when their biggest supplier suddenly stops shipping them parts. There are only a few companies that are firmly in the automotive sector with the right qualifications that can readily provide drop-in replacement parts to Nexperia products.

After the paywall, I’ll provide my perspective of what happens next over the short- and long-term, and a few companies that can serve as viable replacements for Nexperia.