The CPU Bottleneck in Agentic AI and Why Server CPUs Matter More Than Ever

How agent orchestration shifts the CPU-GPU ratio, a framework for scoring server CPUs across reasoning and action workloads, applied to 16 datacenter CPUs from Intel, AMD, NVIDIA, AWS, Google and more

For the better part of two years, CPUs have been an afterthought in AI infrastructure while GPUs got all the attention for training, and more recently inference. In the last 6 months, the rise of agentic AI is proving to be the “killer app” that AI inference needed.

The fundamental needs of computing are shifting as agents handle the work of interacting with AI, and CPUs are fast becoming the overlooked bottleneck. Agentic AI systems chain together tool calls, API requests, memory lookups, orchestration logic, all of which is handled by the CPU while the GPU sits underutilized. In the new era of agents, CPU core count, tasks per core, and memory hierarchy/bandwidth determine GPU utilization, overall throughput and TCO.

The workload characteristics for agents shifts the CPU-to-GPU ratio in a compute tray, rack or cluster, higher, to a point where we may need more CPUs than GPUs, significantly increasing CPU TAM. Nvidia’s announcement that the upcoming Vera CPU can be deployed as a standalone platform for agentic processing, is another signal that the CPU:GPU ratio in the overall cluster is set to go up from what we are typically used to seeing. CoreWeave is set to use standalone Vera CPUs, and Jensen hinted in a Bloomberg interview that “there are going to be many more.”

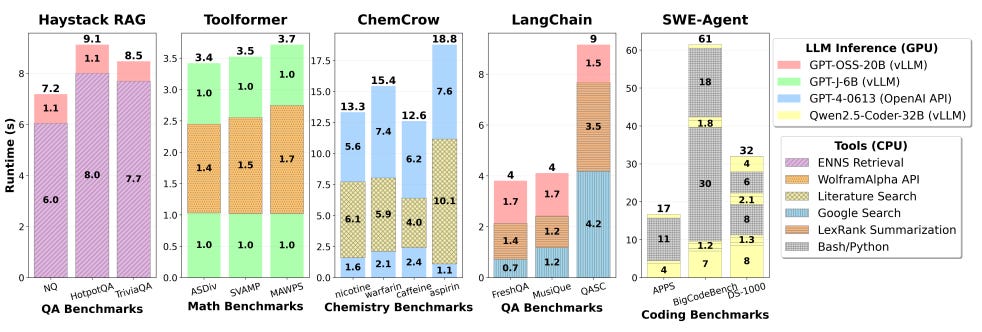

It appears that even Intel did not see this CPU explosion coming from agentic AI. Their most recent earnings call caught management off guard on CPU demand, which tells you just how early we are in this shift. A Georgia Tech and Intel paper from November 2025 estimates that tool processing on CPUs accounts for anywhere between 50-90% of total latency in agentic workloads.

In this report, we will look at the renaissance of the host CPU. We will provide a framework for thinking about when a workload is CPU-bound vs GPU-bound that will serve as a mental model for evaluating any agentic workload. While the common narrative is that CPUs are in short supply and more of them are needed for agentic AI, the specific framing in this article is that CPUs are actually the bottleneck.

Here’s what free readers get:

The thesis (CPUs are the bottleneck, not just “in demand”)

Pure inference vs agent orchestration

The reasoning-vs-action sliding scale

9 CPU metrics defined and explained that classify CPUs for agentic workflows

A reasoning-heavy workflow example + the scoring of the metric table

Here’s what’s behind the paywall:

An action-oriented workflow example + scoring of the metric table

The full CPU comparison table scoring 16 CPUs from NVIDIA, Intel, AMD, and others.

Key takeaways and what it means for Intel, AMD, and the ARM ecosystem

Discussion on x86/ARM structural dynamics

If you don’t have a paid subscription, you can purchase just this article in epub and pdf formats using the button below. Check out all the reports available in this link.

Pure Inference vs. Agent Orchestration

For the last two years, the standard LLM workflow has been a human-in-the-loop cycle: you type a request, wait for a response, read it, think about it, and then act. This loop is inherently slow because the human is the bottleneck.

In the age of agents, the human steps out of the loop and the agents themselves take over this cycle. Based on a broad human input, each agent reads a response, formulates a plan, fires off a tool call or a new inference request, and waits for results. The critical difference is that there are hundreds of subagents per user, all cycling through this loop simultaneously. The faster this loop completes, the faster the agents finish their tasks. A higher number of agents allow many parallel tasks to happen at once, whose outputs then all need to be co-ordinated. The handling and orchestration of agents all happen on the CPU.

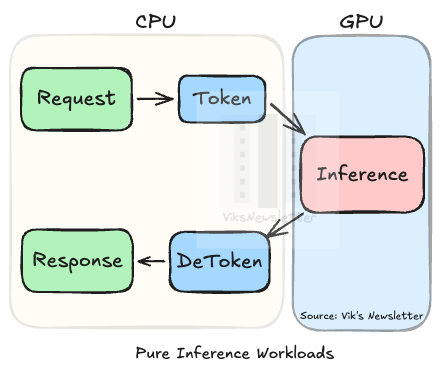

Pure Inference

In a pure inference workflow, the user sends a request, the CPU tokenizes it (converts the text into numerical tokens the model can process), and passes it to the GPU for inference. The GPU runs the tokens through the model, generates output tokens, and hands them back. The CPU then de-tokenizes the result and delivers the response to the user. The figure below shows this workflow.

The CPU’s role as a “head node” is limited to getting the request to the GPU and getting the results back to the user. The compute-intensive work (the matrix multiplications, the attention calculations, the token generation) all happens on the GPU. This is why, for the last two years, the GPU has dominated the conversation around AI infrastructure. In a pure inference setup, the CPU is lightly loaded and rarely the bottleneck.

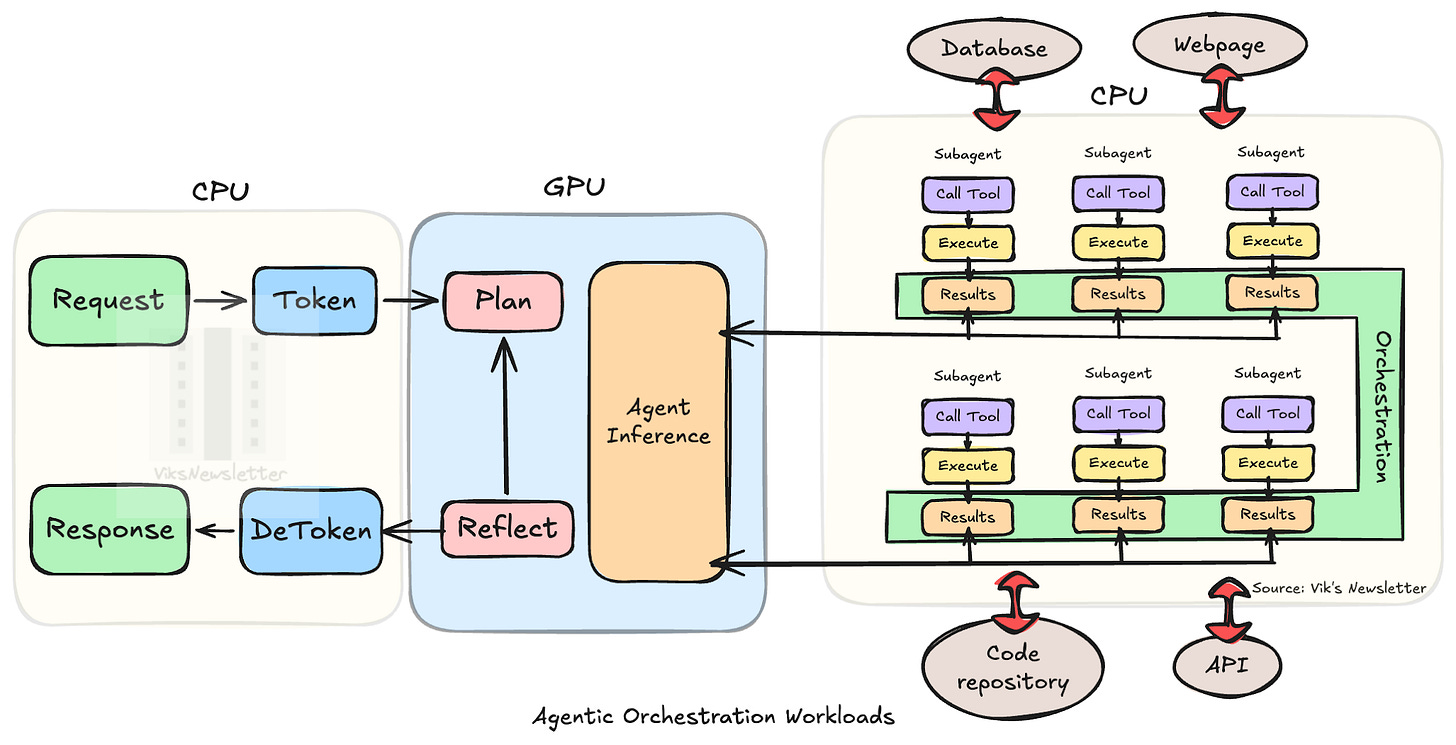

Agent Orchestration

In the orchestration workflow, the CPU goes from being a supporting player to becoming the command layer. CPU performance ultimately dictates how much of the GPU is utilized.

The workflow starts the same way: the user provides a request and the CPU tokenizes it. But instead of generating a response, the first inference call generates a plan of execution. That plan is then carried out by multiple sub-agents running in parallel, each calling different tools and waiting different amounts of time for completion. The CPU orchestrates the relationships between these sub-agents: which are independent, which depend on results from others, and in what order they complete. Each sub-agent may also run its own inference loop based on chain-of-thought reasoning.

Successful agent orchestration requires three things:

A capable CPU running at high enough clock frequency to monitor every token with minimal latency and determine when a sub-agent has finished and integrate those results into other sub-agents as needed.

A high core count so that many agents can run in parallel, working on many tasks at once.

Low latency access to memory for context and intermediate state, making cache design and memory hierarchy essential.

Once all sub-agents complete, the CPU integrates their results and sends them into a reflection inference loop to evaluate whether the original request has been met. If not, another cycle of planning, inferencing, and tool execution begins. This continues until the final result is achieved, de-tokenized, and returned to the user.

Reasoning vs. Action: What Determines the CPU-to-GPU Ratio

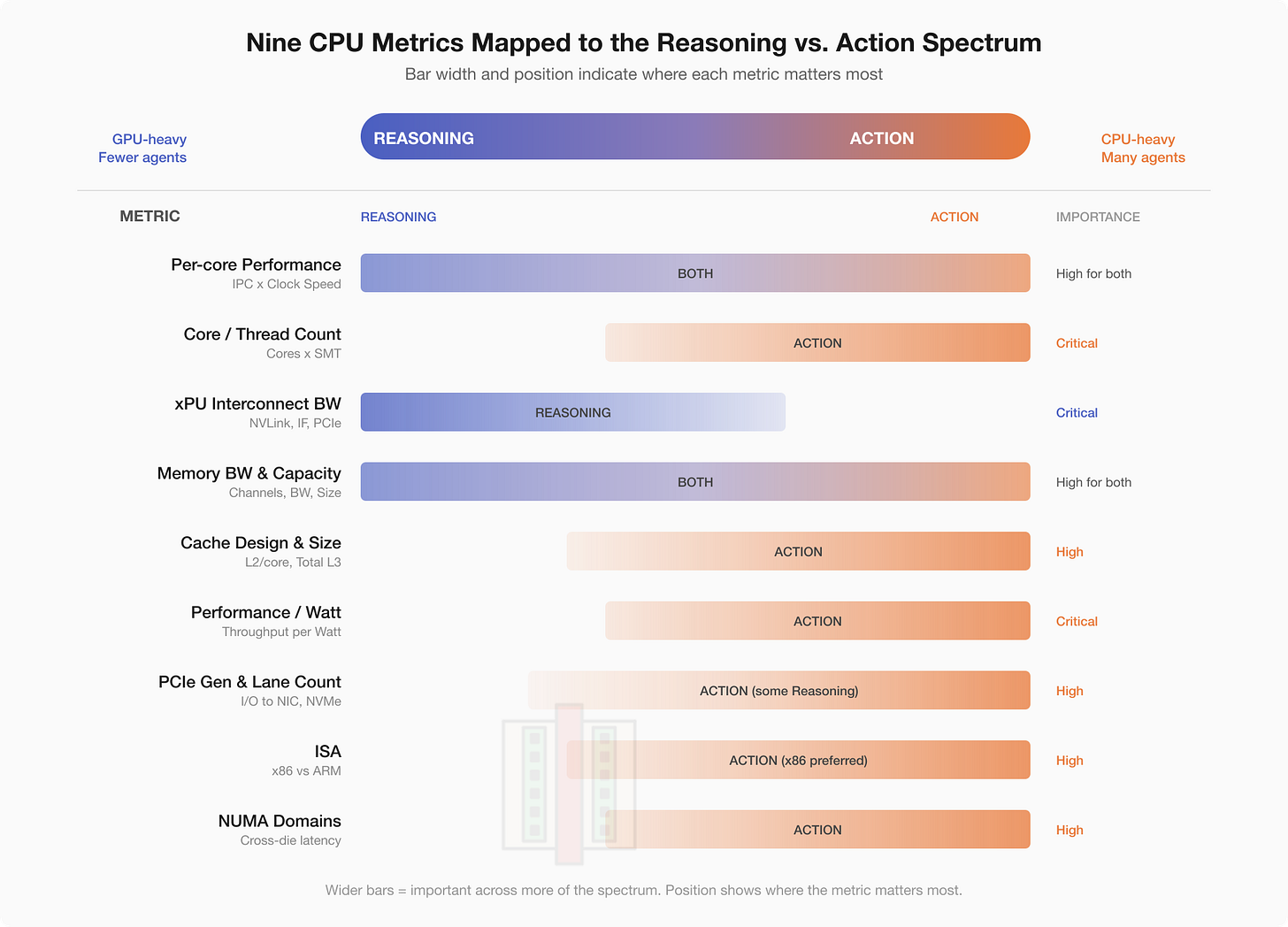

How much CPU versus GPU is used in an orchestration workflow depends on what the workflow actually is. The framework for thinking about this is to view this on a sliding scale as shown in the figure below.

The suitability of any server CPU for the agentic workload is determined by scoring along the following nine metrics.

Per-core performance and clock speed: The CPU needs to make orchestration decisions quickly to keep the GPU fed. It also needs to constantly monitor tokens from each sub-agent to understand when it is done, and what should be done next, all with minimal tail latency.

Core count: Each core let’s say handles one agent, or context switches between a few agents to orchestrate inference loops. Features like simultaneous multi-threading (SMT) allows for more agents per core. Depending on the workload, a single agent can even use multiple cores/threads.

CPU-xPU interconnect bandwidth: Determines how fast the CPU can feed data, or read from the xPU.

CPU memory bandwidth and capacity: Higher memory bandwidth means that larger contexts, KV-cache and inference prefilling can be done with lower latencies.

Cache design and size: More L3 cache implies that memory latency is less noticeable for bursts of random data accesses because the CPU doesn’t have to go off-chip.

Performance per watt: When deploying thousands of agents, per-agent unit economics depends on how much energy it uses to get the required performance.

PCIe generation and lane count: Agents make API calls, hit storage, scrape the web. I/O connectivity to the network and NVMe storage determines tool-call throughput.

Instruction Set Architecture (ISA): x86 vs ARM matters because it dictates what support exists for tool calls. ARM’s simpler RISC ISA provides performance per watt benefits. In addition, the preference for ISA determines what ecosystem you are locked into (Grace (ARM)+GPU from NVIDIA, x86+TPU from Google, or even x86 + NVIDIA).

Non Uniform Memory Access (NUMA) Domains: Modern server CPUs are almost always composed of multiple chiplets to accommodate many cores. Depending on the interconnect technology between chiplets and physical layout, each CPU can have a non-uniform access latency to memory. This implies agents running on different cores can see different memory performance.

For the sake of simplicity here, we will restrict ourselves to cases where matrix operations are only handled by GPUs. So we will leave out features like Intel’s Advanced Matrix eXtention (AMX) where inference can occur on CPUs.

Depending on the kind of agentic workload (reasoning vs. action), certain metrics matter more than others, while others are common across all workloads. We will look at this next.

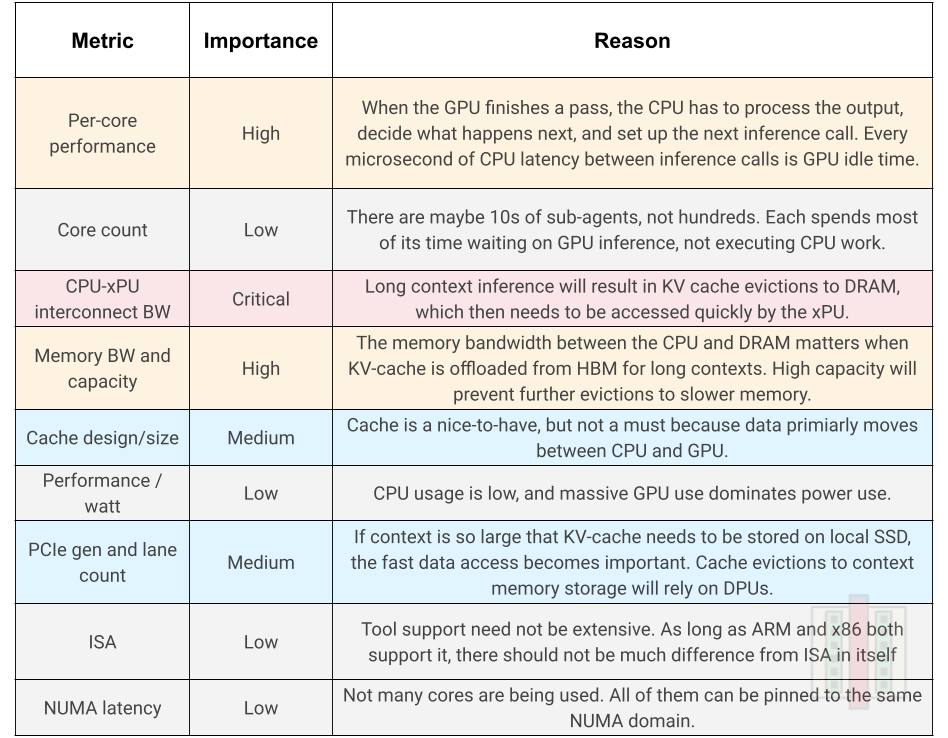

Reasoning-Oriented Workflows

Let’s use an example that is reasoning heavy, focussed on fewer agents, but each agent does extended chain-of-thought reasoning that makes it GPU heavy.

A user asks an agent to produce a comprehensive analysis of the DRAM market outlook for 2027 based on a large collection of market research reports provided. The orchestrator plans 10 sub-research areas. Each sub-agent runs a long chain-of-thought inference loop, generating hundreds or thousands of reasoning tokens as it synthesizes its area. Occasionally a sub-agent retrieves a document or does a web search, but 80%+ of the compute time is spent in inference. The agents are thinking, not doing and once all sub-agents finish, a final reflection pass synthesizes everything into the output.

The table shows the relative importance of each metric and why.

An example of a CPU well suited to heavy reasoning workload is NVIDIA’s Vera CPU for the following reasons:

Per-core performance: 88-cores of fast, custom Olympus ARM cores with multi-threading. Not the highest core count, but good per-core performance.

CPU-xPU interconnect: NVLink-C2C at 1.8 TB/s bidirectional. Coherent memory sharing lets the Rubin GPUs read directly from CPU memory as if it were their own. This is the defining feature that makes Vera a reasoning-end CPU. Nothing else comes close.

Memory bandwidth and capacity: 1.5 TB of LPDDR5 across 8 SOCAMM modules at 1.2 TB/s. Massive capacity for KV-cache expansion.

Although the choice of Vera locks you into the NVIDIA ecosystem, and the ARM architecture makes tool compatibility questionable, the massive interconnect bandwidth to GPU, fast cores, and lots of DRAM, makes it score high on every metric that matters for reasoning-heavy workloads.

After the paywall, we discuss:

An action-oriented workflow example + scoring of the metric table

The full CPU comparison table scoring 16 CPUs from NVIDIA, Intel, AMD, and others.

Key takeaways and what it means for Intel, AMD, and the ARM ecosystem

Discussion on x86/ARM structural dynamics