Why Documentation is the Missing Link Between AI and Chip Design

Chip design has always depended on unwritten know-how. To bridge tribal knowledge and machine intelligence, engineering culture needs new ways to capture and share the messiness of real design work.

Welcome to the weekday free-edition of this newsletter that is a small idea, an actionable tip, or a short insight. If you’re new, start here!

If you’re not a paid subscriber, here are some posts from last month you’re missing out on:

The manufacturing challenge behind Nvidia’s plan to mount AI chips directly on PCB platforms

A primer on transformer architecture: model parameter calculations, estimating GPT-5 architecture

Bridging the AI Knowledge Gap for Chip Design

Chip design knowledge is tribal.

The tacit know-how in daily tasks are the engines of engineering creation. Much of the work depends on the unwritten rules engineers pick up on the job. This is what employers mean when they ask for “experience.”

Now, chip design teams have a new premise: AI. Leveraging machines to replace engineering work is the dream. It eliminates hiring, work-life balance, promotions, job titles, motivation, burnout, and a host of management “headaches” that comes with having people around.

But there’s a problem. To teach machines, tacit knowledge must first be documented. And documentation is the one thing engineers dislike most.

I personally enjoy converting technical thoughts into text. I do a lot of it for this publication and it has helped me understand technology better. But under design deadlines, documentation becomes an afterthought. It rarely gets its own time, and so remains a second-class citizen in engineering.

Yet, in the age of LLMs, it is exactly what we need. Machines learn through language and data. Without structured documentation, they cannot absorb useful knowledge. The question is: how do we turn existing documentation into something machines can learn from?

Mapping the Engineering Documentation Landscape

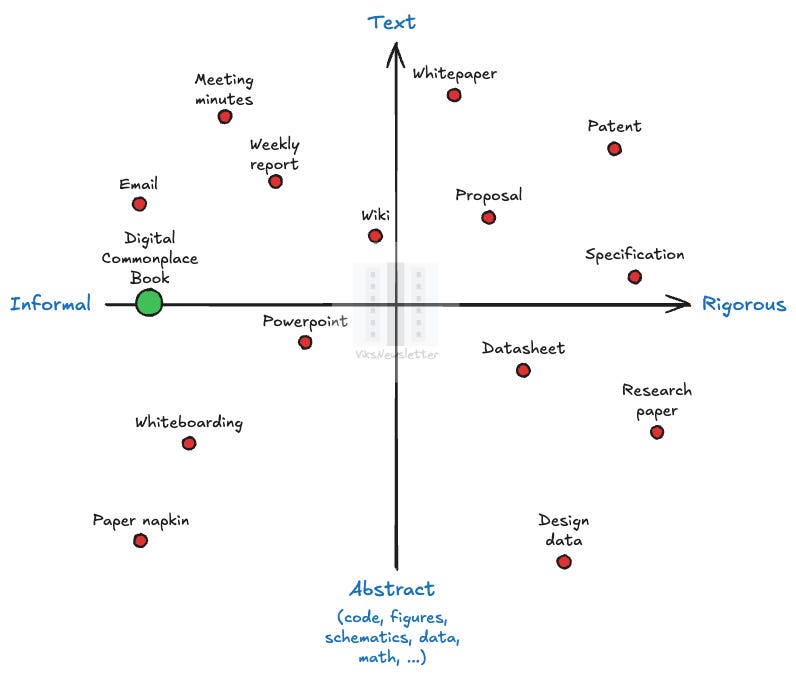

The following 2×2 grid shows the various types of documentation engineering teams often generate (we will discuss the digital commonplace book separately in the next section.) One axis shows the degree of formality in the documentation, which is directly correlated to how easily it can be created. Some forms of documentation are formal and rigorous, like research papers. Others are quick and informal, like emails.

The most popular format in the chip design industry is sadly a powerpoint, which lacks both rigor and context to make it useful outside the meeting it is originally used in. Though it is useless in capturing tacit engineering knowledge, most company documentation still lives on in this format.

Interestingly, all the documentation forms shown in the chart exist within a chip design company. Every digital asset ever created, whether it is whiteboard scribbles, email, meeting minutes, schematics, or complete reports, now represents a useful artifact that can be used to construct intelligence internally in a company. With vector embeddings and Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), all of this could be stored and made useful across a company.

While this would be a leap forward compared to a powerpoint driven documentation culture, innate knowledge of chip design comes from the unfiltered thoughts running in an engineer’s mind while working on a design. But how do we capture that?

The Digital Commonplace Book

The ideal format to capture tacit, tribal knowledge is a completely informal but digitizable stream-of-consciousness artifact that balances both textual explanations and abstractions based on code, schematics, data and math.

This is the digital equivalent of a commonplace book — which is basically a lab notebook/scrapbook in which you collect all your insights, notes and diagrams. Many notable scientists and engineers have maintained notebooks that show their detailed process of thinking through difficult problems.

In the online version of the Thomas Edison papers, you will find an immense catalog of every notebook Edison ever maintained. They are a mix of text and images that provide deep insight into the mind of a great inventor. Similarly, there is Charles Darwin’s meticulous note taking on his observations about the natural world.

A more notable and recent example is the notebook of famed French mathematician, Alexander Grothendieck. He believed that every one just flattened mathematics by just showing the end result. Instead, he maintained a detailed account of all the thoughts, emotions, mistakes and tangents that he took in doing the work. Hendrik and Johanna Karlsson who write Escaping Flatland have an excellent piece on Grothendieck which I recommend reading.

A digital commonplace book with a collection of voice transcriptions, screenshots and code snippets goes a long way into building insights into how the actual engineering is done. How can this sort of technical ‘notebooking’ be inserted into engineering culture?

Transform weekly reports into LLM-ready data streams

It is easier than ever to create, query, and refactor text-based documents with the advent of LLMs. This could be extended to audio and video formats too. The key is to leverage this in an engineering organization.

Weekly reports have been the mainstay for reporting on technical progress. These are mostly skimmed over or used to create status reports for higher levels of management, who then gloss over it themselves. Weekly reports consume many hours without adding lasting value.

A better approach is to replace weekly reports with raw digital artifacts intended only for LLMs.

Each team uses a central documentation platform (not sharepoint) that accepts all modes of data: voice, text, screenshots, video captures, meeting minutes, and 1:1 discussions. Every engineer within the team is then encouraged to input any and all forms of thoughts, experiments, failures, successes, or literally any media into this platform without any expectation of formatting, structure, or logical sequence of thought. The LLM running on the company premises then organizes all this media into logical blocks, organizes the information, and assists in retrieval at any point. The hope, of course, is that hallucinations will continue to decrease as LLMs evolve.

Closing Thoughts

Building the bridge between chip design knowledge and machine intelligence needs us to deal with the messy, incoherent, confusing, and even wrong intermediate steps before machines can assist with complex design tasks in any meaningful way.

The real challenge is not technical, but cultural. Engineers must be encouraged and incentivized to document their thoughts, however unpolished. Informal notes are better than silence. There is always the obvious question of why anyone in their right mind would teach machines to do what they consider their bread and butter.

Regardless, AI cannot replace chip design engineers in the absence of the unwritten rules of actual engineering work. However, with some cleverness, I think we can use machines to improve the quality and speed of our design work.

Love this post? ❤️ Think I’m off my rocker? 🤪 Let me know in the comments.

While I agree that your approach would indeed make chip design a lot more approachable (digestible?) for AI, it also faces the same obstacle that is IMHO a key reason why documentation is currently mediocre at best:

people don't like to obsolete themselves. Poor documentation is like a virtual moat that helps keep the barbarians out.

It would be interesting to know how, for example, Nvidia has dealt with this. I picked Nvidia as they started using AI tools to assist their chip design earlier than most.

Really great article! Although I am just an engineering student right now, I feel I indirectly learnt the importance of documentation, or just writing down your thinking in a notebook, to learn better and help in becoming a better engineer overall.