Why Getting a Semiconductor Job Is Harder Than It Should Be

Understanding the structural bottlenecks behind hiring, education, and outdated industry practices, and some helpful suggestions to navigate the career landscape.

Welcome to a 🔒 subscriber-only Sunday edition 🔒 of my weekly newsletter. Each week, I help readers learn about chip design, stay up-to-date on complex topics, and navigate a career in the chip industry.

As a paid subscriber, you will get additional in-depth content, and also get to suggest topics for this newsletter using this form. We also have student discounts and lower pricing for purchasing power parity (see discounts). See here all the benefits of upgrading your subscription tier!

A quick note: I am working on a long article on advanced packaging that will go out in the next week or two. Packaging technology is central to the move to silicon disaggregation and chiplet integration, but the entire landscape is fragmented with many players developing their own technologies and creating their own marketing terms. It is a challenge to weed through the chaos, but hopefully I’ll make sense of it soon and find a way to explain it in clear terms. Stay tuned!

Just about a month ago, I wrote an article about why the semiconductor industry is failing to attract new talent. It became the second highest read post in the 16 month history of this newsletter.

In it, I had a survey link asking for feedback about the problems in the semiconductor industry. Nearly all responses resonated with at least one aspect of my original post, and suggested many additional aspects that I originally missed. The only stance I had to modify from comments to my previous post was the aspect of compensation. Software does pay significantly more. The link is still active if you want to send in your thoughts.

Everyone in semiconductors agrees there’s a hiring problem; managers, prospective candidates and working professionals all have difficulties in finding the right fit. But ask why and you’ll get many subjective perspectives none of which are complete.

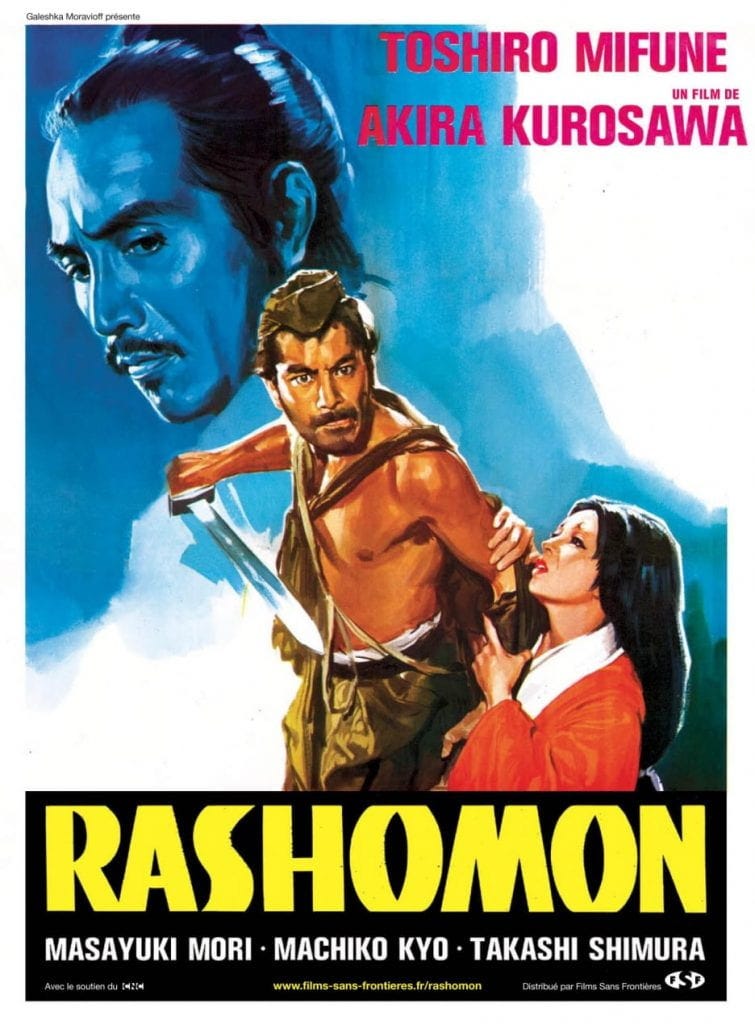

This is the classic Rashomon effect which refers to the phenomenon where different people have contradictory interpretations of the same event, based on their own subjective perspectives. It’s named after Akira Kurosawa’s film Rashomon, in which four witnesses recount a murder, each with a radically different version of the truth. If you haven’t seen this movie, you should.

Today’s essay is a collation of responses to my survey question asking what problems people see in the semiconductor industry — particularly related to building a career in it. It also contains my reinterpretation of those responses in an attempt suggest solutions to circumvent those problems. I cannot escape the Rashomon effect either. Like everything else, this is just another version of the truth.

Before we dig deep into what might constitute potential career bottlenecks in this post, it is helpful to understand that the semiconductor industry is cyclical in nature. There are periodic boom-bust cycles that affect hiring rates and compensation. The last couple of years have seen a slowdown in hiring with many companies having layoffs; the exception being AI-centric hardware providers. The systemic problems we will discuss in this essay go beyond short-term hiring market, at least in my opinion.

Here is what is contained within this post:

Bottleneck #1: The talent pipeline is broken at both ends. A chicken-and-egg situation where education programs are misaligned with what the industry wants, and the industry is secretive about technology and its modus operandi.

Bottleneck #2: The bar for entry keeps rising with little payoff. Qualification inflation means that every job asks for advanced degrees which is reducing the available talent pool. But higher degrees don’t always mean higher pay.

🔒 Bottleneck #3: Industry practices for hiring and retention are archaic: Industry hiring practices might be missing great candidates because semiconductor skills are complex. Career ladders in many companies demotivate more people than encourage people to work hard and climb them.

🔒What you can do to overcome these bottlenecks: Finding a way around these challenges involves looking beyond the obvious. A career in engineering is not just fabs and chip design; there is a whole lot more. You may not have to play the game of advanced degrees, and why reputation matters more than resumes.

Read time: 12 mins

Bottleneck #1: The talent pipeline is broken at both ends

Breaking into the semiconductor industry is harder than people are led to believe by the news cycles which tout billions of dollars of investment by various governments around the world in semiconductors in an effort to secure their supply chains.

The reality is that when students emerge from educational programs, they often find that getting internships and landing jobs is harder than they thought. If there is so much money in chips (or maybe not so much anymore), then where are the jobs? Several respondents to my survey said that they have not received interview calls for months after graduating. Where then does the problem lie?

There is a real possibility that students are simply not acquiring skills that are aligned with the industry's needs. To the extent that this is true, I blame the lack of openness, guidance and mentorship in the semiconductor industry. What the semiconductor industry fails to do is to provide adequate access to technology creating a chicken-and-egg scenario where you can’t learn the skills unless you land the job. Thus potential candidates are at an impasse when it comes to breaking into semiconductors.

On the other hand, educational programs often do not provide all the training the industry needs either. Chip design, for example, requires access to tapeouts and EDA tools which are cost prohibitive for many learning institutions. Open-source PDKs like SkyWater SKY130, IHP's SG13G2, or NCSU FreePDK are useful for learning but what companies are looking for is someone who can hit the ground running in a state-of-the-art process technology with an awareness of industry standard tools, workflows, and practices. The open-source ecosystem does not provide this experience yet. Even when potential candidates do persist, they face increasingly steep qualification hurdles.

Bottleneck #2: The bar for entry keeps rising with little payoff

I still remember my internship mentor at Texas Instruments telling me in 2008 that he is happy that I decided to pursue a PhD instead of taking the job I was offered after my masters. It was a hard choice to pass up a 6-figure offer for life in graduate school while all my friends were buying shiny new cars with their first paychecks.

My mentor’s point was this: a PhD opens doors to work on the cutting edge of the industry; a Masters degree would put one squarely as a cog of the great industrial machine. This seemed convincing to me at the time and I still do agree with his sentiment to a large extent. I also consider myself lucky to have received good mentorship at the right time. There are many jobs in the semiconductor industry that requires the level of specialization a PhD offers. Over the years, I have come to believe it is a double-edged sword in several ways.

Specialization can get so localized to a tiny subfield of the engineering space that there are too few jobs that require it.

The extra specialization does not offer significantly higher pay to justify half a decade or more of lost opportunity cost from a full-time paycheck.

As a PhD, you may still become a cog in the machine.

The other issue is a moving goalpost in terms of educational requirements for jobs. Positions that needed Bachelors degrees before now need a Masters degree at the minimum. Many design jobs even ask for PhD degrees and depending on the role, they even ask for 5-10 years of experience on top. This kind of qualification inflation misaligns the incentives between employer and candidate in two ways:

The candidate pool for jobs shrinks because not everyone wants to, or is able to spend a good part of a decade in graduate school, especially when they know that the marginal payoff is not that much more.

Employers do not find the right candidate because the specializations at the PhD level are already narrow. They are forced to hire PhDs from adjacent fields if they happen to make it past archaic HR screening processes.