AI Datacenters Drink More Water Than You Think

Why the "2.5 burger joints" metric doesn't tell the whole story, carbon-water footprint tradeoffs, and why long-term datacenter water usage looks very different.

You can download this post as an epub/pdf for free using the button below. Paid subscribers get every deep-dive in downloadable digital formats. If you’d like to only purchase specific reports, you can see the growing digital asset collection here.

Note: This post is an exploration around a SemiAnalysis article on water use. I discuss tradeoffs I feel are not discussed in the original post. It’s not meant to minimize their work in the semiconductor space. I am a regular reader, and appreciate all the content they put out.

The “water footprint” of AI datacenters has become a hotly debated topic. The most widely cited study on the issue is a paper titled “Making AI less thirsty: uncovering and addressing the secret water footprint of AI models“ by UC Riverside and UT Arlington researchers, set the stage by stating that GPT-3 needs to “drink” a 500 ml bottle of water for roughly 10–50 medium-length responses.

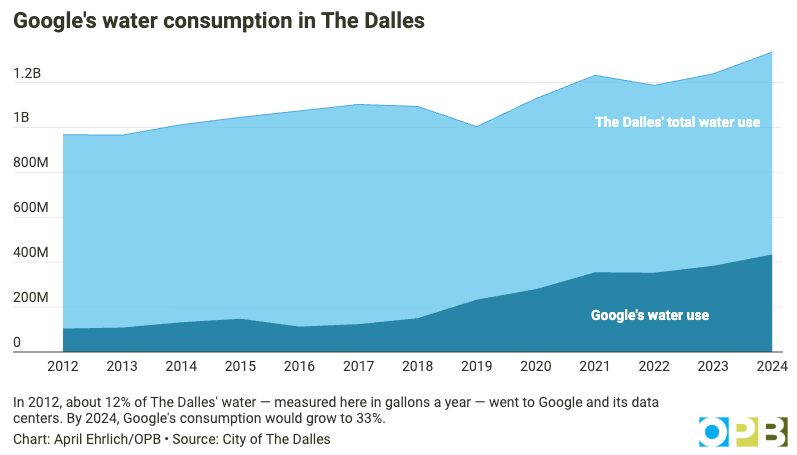

This debate reached a boiling point with the widely-reported controversy surrounding Google’s datacenter in The Dalles, Oregon, where the company initially refused to disclose its water consumption, claiming it was a trade secret. Subsequent legal battles eventually revealed Google was using a quarter of all the water in the entire city. The most striking development is The Dalles’ recent attempt to expand its water reservoir by pulling from the Mount Hood National Forest, an action that drew immediate concern from environmental groups.

In this post, we take a closer look at the SemiAnalysis article that promises I can use “Grok for 668 years, 30 times a day, every single day” for the water footprint of eating a single burger. I know I’ll still take the burger, but there are some important consequences of comparing datacenters to beef that we should talk about. I recommend you read the original article first.

We’ll explore how water use and carbon footprint are finely intertwined, and how datacenter design choices affect both. Not all infrastructure buildouts are reducible to burger metrics.

The Tokens-per-Burger Comparison

A SemiAnalysis post titled “From Tokens to Burgers: A Water Footprint Face-off,” states that a datacenter like xAI’s Colossus 2 consumed the same amount of water as 2.5 In-and-Out burger restaurants, a popular fast food chain in California. David Sacks identified it as a “narrative violation” - a series of tweets he puts out whenever there is something contrary to popular opinion. Although there is nothing wrong in flagging contrarian takes like Sacks did, it captures the attention of millions and unintentionally provides a means for policy makers to unknowingly understate the importance of water use in AI datacenters.

The dissonance in the water commentary is stark. If water in datacenters is a non-issue, then why tap into national forest reserves? This begs the question: Is xAI’s Colossus 2 somehow different from Google’s Oregon datacenter? More generally, how do datacenter design choices affect water use?

First, it is important to understand that water usage comes from three places:

To cool the chips in the datacenter

To generate power to power the datacenter

To make the chips that go in the datacenter

We’ll leave #3 out of it because it applies to the whole semiconductor industry. Let’s just focus on #1 and #2.

Google’s Oregon datacenter water usage comes from the use of evaporative cooling to cool their chips (high water usage), while their power source uses hydroelectric power from the grid via the Columbia River dams. Hydroelectric power itself does not consume water if it is running water, but evaporation from dams is a major problem and puts water consumption for unit energy produced as energy at >10,000 gal/MWh.

xAI’s datacenter uses more modern dry or adiabatic cooling methods that require much less water, and on-site aeroderivative turbines for on-site power generation that require zero water. SemiAnalysis states in their article:

In the case of Colossus 2, the datacenter currently uses aeroderivative simple-cycle turbines from Solar Turbines with no steam or combined cycle, which means no water is consumed during the power generation process. The water profile could change if future CCGT turbines are included, but for now let’s keep the current layout.

They do acknowledge that other turbine choices could affect water profile, but don’t say how. Just looking at the sources of water use for two datacenters shows vastly different usage patterns. Inherent in the discussion is the tradeoffs between carbon and water footprints based on the technologies used, which we will revisit at different points in this article.

Therefore, we must not extend the “2.5 in-and-out restaurants” metric to every possible datacenter that can ever be built now or in the future. The burger joint ratio may be true in the short term, but in the long run, the conclusions might be entirely different. Google vs. xAI was just an example of two datacenters with different water profiles.

Carbon vs Water Tradeoff in Power Generation

To understand why water is so intertwined with power generation, we need a quick thermodynamics primer. There are two thermodynamic cycles that matter here: the Brayton cycle and the Rankine cycle.

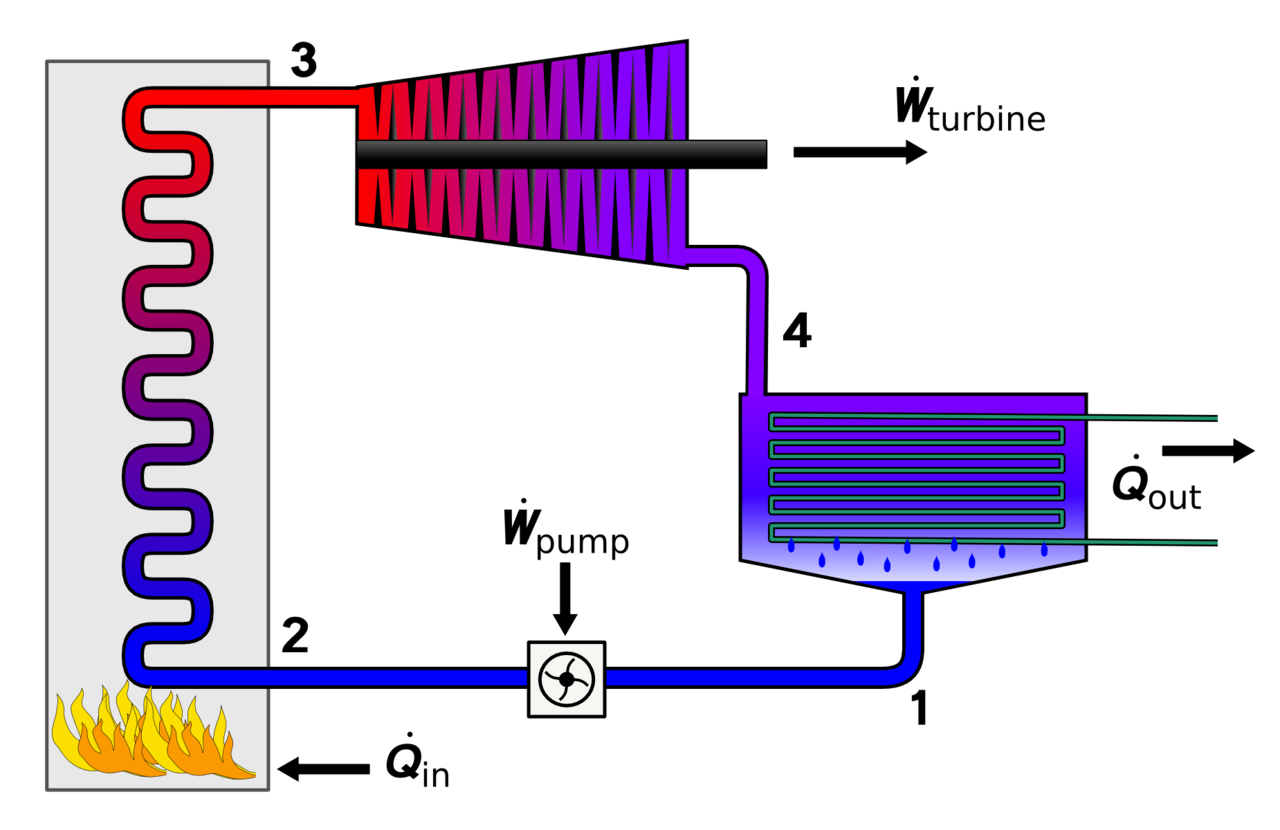

Rankine Cycle

The Rankine cycle is the workhorse of large-scale power generation. Heat from burning coal or from nuclear fission boils water into steam, that steam drives a turbine, and the turbine generates electricity. The conversion is: thermal → mechanical → electrical. Coal and nuclear plants run on the Rankine cycle, and they are water hungry because steam is the working fluid. Nuclear reactors are actually more “thirsty” than coal plants due to their lower thermal efficiencies, primarily stemming from lower reactor temperatures used for the safety of reactor walls.

Brayton Cycle

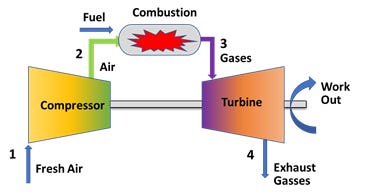

The Brayton cycle works differently. Air is compressed, fuel is burned in it, and the hot expanding gas drives a turbine directly. No steam is used and hence no water is needed. This is what aeroderivative simple-cycle turbines use for behind-the-meter power at datacenters (more on this in the next section).

Natural gas is the one fuel source that can use both cycles.

In a simple-cycle configuration (Brayton only), natural gas is burned to spin a turbine and generate electricity.

Combined-Cycle Gas Turbines (CCGTs) use the Brayton cycle to burn gas, drive turbines and generate electricity. But they also capture the hot exhaust and feed it into a heat recovery steam generator to drive a second steam turbine (Rankine cycle) on top of the first.

This is how CCGTs hit ~60% efficiency compared to ~35-40% for simple-cycle, but the steam side needs water for cooling. CCGT water consumption is typically 400-1,200 gallons/MWh. Most grid-scale natural gas plants today are CCGTs because the efficiency gains justify the water and infrastructure costs.

Electrical Grid Bottlenecks and Behind-the-Meter Power

The fundamental problem is that the grid can’t keep up. Between power plant buildouts and interconnection infrastructure (transformers, transmission lines, substations), wait times range from 4 to 12 years. Datacenters don’t have that kind of time because billions in invested infrastructure needs to generate revenue quickly.

The solution is to generate “behind-the-meter” (BTM) power on-premises to power the datacenter. Since datacenters are not always located near large bodies of water, there are essentially three ways to generate electricity without massive water use:

Using natural gas to power jet engines and produce electricity → aeroderivative simple-cycle turbines using the Brayton cycle

Use electrochemical reactions to convert natural gas into electricity → solid oxide fuel cells

Use massive solar panel arrays and energy storage systems to power datacenters.

We will discuss methods 1 and 2 in moderate detail because the common factor between both is that they produce CO2 in the process of power generation. These methods are far from the carbon neutrality datacenters hope to achieve in the coming years. Method 3 using solar power deserves its own article, and is out of scope in this post.

Simple Cycle Turbines

Aeroderivative simple-cycle turbines from GE Vernova, Solar Turbines or Boom, produce electricity by burning natural gas to drive turbines. They’re called “simple-cycle” because there is no intermediate steam cycle (Brayton only). Although they do not consume water, they are less efficient compared to CCGTs used in utility power plants. Their low water use comes at the cost of a higher carbon footprint, a tradeoff not addressed in the SemiAnalysis article. The burning of natural gas produces prodigious amounts of nitrogen oxides (NOx) that have an immediate impact on the local environment.

What happened in xAI’s Colossus 1 in Memphis is a cautionary tale. The company deployed 35 gas turbines on-site to power its GPU cluster before a grid connection was available, and local residents quickly raised alarms about the stench and air quality. The Southern Environmental Law Center argued the turbines violated the Clean Air Act even if the methods were implemented to reduce oxide pollutants. These methods are:

Dry Low Exhaust/NOx (DLE/N): This technology uses a pre-mixed ratio of largely air with a little fuel mixed in to lower combustion temperatures. This makes it difficult to run the turbines at partial load, and if the fuel ratio drops below threshold, the flame goes out (called Lean BlowOut, or LBO) and electricity generation stops. Although companies have engineered this into their turbine pretty well, it does not prevent the emission of other pollutants such as benzene.

Water Injection: Another way to reduce the flame temperature in the turbine is to inject demineralized water into it. Thus, simple-cycle turbines can also consume water at the rate of 25-50 gal/min per turbine. 20 turbines (each with 52-58 MW capacity like GE LM6000 PF+ turbines) used to power a GW datacenter can consume 1 million gallons of water per day just to reduce emissions – a carbon vs. water footprint tradeoff.

The Colossus 1 datacenter did not use water injection because it was built in record time, and setting up water treatment infrastructure would have delayed the project. Once a new 150 MW substation from Memphis Light, Gas and Water came online, xAI began removing the turbines since they were no longer needed as the primary power source. About half remain to power Phase 2 GPUs until a second substation is completed, at which point the remaining turbines get relegated to backup duty.

xAI’s Colossus 1 datacenter is a case study on how energy infrastructure can be quickly deployed with immediate short term environmental impact. In the long term, it will always make sense to switch over to grid infrastructure when it becomes available. Based on how grid power is generated, Colossus 1 now has a water footprint it did not have earlier when it only used aeroderivative turbines.

Solid Oxide Fuel Cells

Solid Oxide Fuel Cells (SOFCs) use a solid oxide electrolyte to convert natural gas into electricity through an electrochemical reaction and not via combustion, and virtually eliminate NOx pollutants. They have higher electrical efficiency (>50%) compared to aeroderivative turbines (35-40%), require no water for power generation, and can be deployed much quicker than turbines.

SOFCs are also very energy dense and can fit a large amount of energy into a small physical footprint. Bloom Energy - a predominant player - markets their “100 MW per acre” configuration by vertically stacking power sources, which offers about a 2x density advantage over turbines and a 100x advantage over solar panels.

We’ll get into Bloom Energy another time; they are a promising company and are well positioned to power the massive AI infrastructure spend that hyperscalers have committed to in 2026. SOFCs are >2x more expensive on a capex basis compared to aeroderivative turbines, but the simplicity in permitting and lower land use makes them attractive.

Natural Gas Bottlenecks

BTM power generation technologies deployed on-site are intended to be a bridge between the present and the future date of interconnection to the grid. Aeroderivative turbines and SOFCs will live on as backup energy sources, or to provide power boosts if the grid is unable to supply sufficient power. They will not work as long term power sources for datacenters for one simple reason: availability of natural gas.

If dozens of GW-class datacenters all use natural gas on-premises to power their infrastructure, the next big bottleneck on the horizon will be natural gas pipelines. Building gas pipelines is as difficult as building electrical interconnection infrastructure and can take years from start to finish. Pipeline ruptures are usually single points of failure while electrical grids have built-in redundancy. BTM power plants only shift the electrical infrastructure bottleneck to gas infrastructure.

Nuclear Inevitability

This brings us to the only, inevitable1 option for large-scale, zero-emission power: nuclear energy, assuming that electrical grid infrastructure will eventually be built out to support all planned datacenters. Nuclear power plants are the ultimate choice for datacenter power for a several reasons:

It is a carbon-free power source because it relies on fission, not on fossil fuels to drive CCGTs.

It provides a 90%+ capacity factor – a metric that quantifies how much energy is produced compared to the maximum possible energy. In comparison natural gas is 50-60%, and renewable energy sources are <40%.

They can run 24/7 unlike renewable energy sources that only generate power between 6-9 hours a day, and then need expensive storage systems to hold that power

They have a minimal land footprint, significantly lower than the other carbon-free renewable energy sources.

A small amount of Uranium can produce a lot of energy. There are no real supply chain concerns.

Despite all these benefits, nuclear power uses more water than coal power at ~670 gallons/MWh. Most pictures of nuclear power plants always have steam coming out of the cooling towers for good reason.

With BTM gas-powered power plants, we might only consume “2.5 in-and-out restaurants” worth of water today. But this is merely temporary, and we must be cautious to not dismiss the requirements of water in datacenter power generation in the long run. To power a GW-class datacenter like Colossus with nuclear power, it takes 0.67 million gallons of water per hour, or 16 million gallons per day – which is 16 times higher than SemiAnalysis’ estimate. There is the other issue that AI datacenter water consumption is highly localized, while beef production is much more spread out.

Nuclear power is still highly sought after to power datacenters. BTM power generation can be based on nuclear power if a datacenter is built on the same campus as a nuclear power plant. This bypasses the need for grid infrastructure, while still having all the benefits of nuclear power - a win-win situation. This is exactly why AWS purchased the Cumulus data center campus from Talen Energy next to a nuclear power station in 2024, for $650 million.

The end-game of nuclear energy is the use of Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) to power datacenters: Nuclear BTM power. These small nuclear power plants can be located close to datacenters, greatly minimizing losses in power transmission while not having to wait for interconnection grids. They’ll still use water, but they can be “right-sized” based on local water supply infrastructure and power needs. Companies like Kairos Power have signed a multi-plant agreement with Google to deliver clean, nuclear power by 2035. X-energy and Nu-scale are other companies to watch out for in the nuclear energy space. These technologies are like Iron Man’s Arc Reactor powering his suit. It’s just that we need these for AI datacenters.

What do you think of the water usage in datacenters? Leave a comment below.

Solar power is promising no doubt, and not to be ruled out as an alternative to nuclear energy.