How to Escape the Corporate Rut for Midcareer Chip Engineers

Simple ideas to keep your paycheck, grow skills, and enjoy the work again.

Welcome to the weekday free-edition of this newsletter that is a small idea, an actionable tip, or a short insight. If you’re new, start here!

If you want to send in your questions that I can discuss on this newsletter, use this link. Please provide substantial context instead of one-liners.

A reader wrote in to me essentially asking me the following:

Q: I’m a backend VLSI engineer with 7 years of work experience with a narrow, repetitive and hectic job scope. I do not feel like I’m growing in my current role, and the opportunities to learn and experiment are few. I’m exploring analog/mixed-signal design through self-study and training, but I’m unsure where this will lead me. How should I plan this transition, and is it too late to make a shift?

This is a scenario that a lot of people find themselves in, and when put in context of careers and people in the chip industry, it will start to make a lot more sense.

Let’s talk about this, as applied to the chip industry because that is what I know best.

The Promise of a Successful Career

Most people pursuing a career in engineering do so with an end-goal in mind: study interesting things in school, do as well as possible, and find a high paying job at a name-brand company.

Some who like the technical aspects may pursue an academic career. Others will likely do well enough to land a job as a junior engineer in a company. The interview process often tests the limits of knowledge you have acquired in your student years, and passing it successfully can make you think you are ready for real-world work.

Well, it does not work that way.

You see, chip design is such a complex, intricate, and detail-oriented process that it often takes hundreds of engineers to successfully make a product. What this means for you is that you have been hired to repeatedly do a tiny but important task that will eventually play a part in the success of the chip. Your technical background from school is a good foundation, but you will still be trained to do that tiny, important task.

Good management will keep your individual efforts well connected to the end result, and that keeps you motivated as long as you can see and feel the excitement of doing meaningful work. In big companies, it is often hard to link your task to the final product. Scale and complexity get in the way. Without the justification that what you do has any impact, most engineers start to feel like they are a cog in the great corporate machine. And rightly so.

From the outside looking in, you have made it as a successful engineer: good tech pay at a good company. But there is a deep, intellectual dissatisfaction that eats away inside.

The Game of Life: MegaCorp Edition

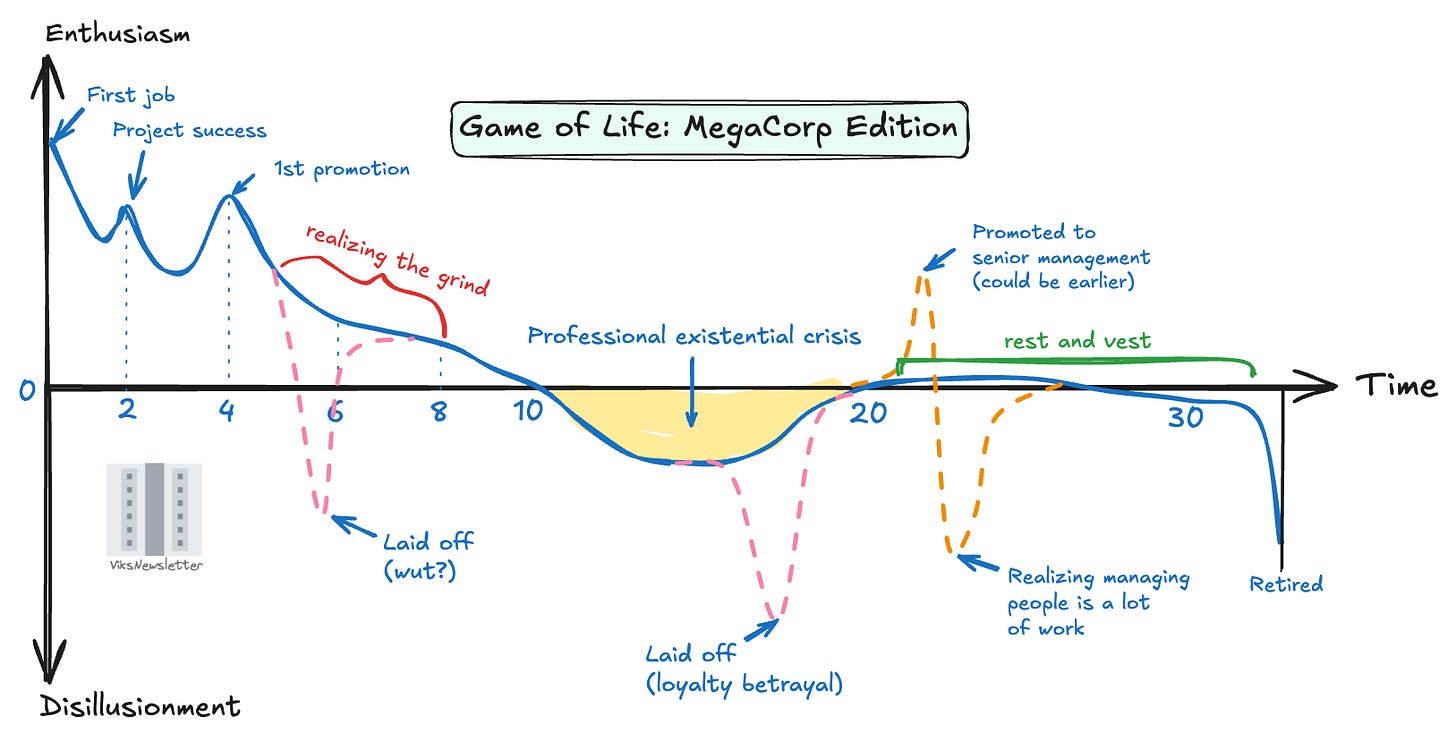

Most people who enter the corporate workforce do not encounter the dissatisfaction right away. It is right around the 5-8 year mark that it creeps in, just like it did for the reader who posed the question. But the feeling is part of a greater pattern — one possibly explained by the popular board game: The Game of Life — for which a corporate edition would be a smash hit among the hordes of jaded tech workers in MegaCorps. I’d imagine it would look something like this.

0-10 years

The first five years are the time of greatest enthusiasm in a corporate career. The world feels like an open book where anything is possible. The thrill of seeing your chip land in the hands of millions (even if you played a small part in it), the Kool-Aid of company all-hands meetings, your first promotion, and most importantly the impressive paycheck that is getting you out of school debt, keeps you going.

Rapid hedonic adaptation soon establishes the new baseline. What once impressed you does not anymore, but suddenly you realize you’ve been doing the same old tasks at work. At this point, some people might change companies looking for new exciting roles, only to realize it is a similar grind just at a different place.

10-20 years

After a decade of doing this, priorities often start to shift as family takes center stage. As your seniority rises, so do your responsibilities, which you now have to balance against family commitments. When professional crisis morphs into a midlife crisis, burnout becomes a real possibility. You take up new hobbies you did not have time for earlier — biking, golf, or woodworking — to create diversions from hectic engineering days. In a 20-year run, there is also a high chance you’ve been part of multiple layoffs and possibly affected by at least one. You now understand the industry.

20-30+ years

The last decade might involve a stint in senior management, which can be very lucrative and also stressful when you have to deal with people and high-stakes deliverables. Regardless, there is little incentive to make company moves at this point — the thought of interviewing with someone half your age is not exactly motivating. This is when engineers slide into a “rest-and-vest” mentality — collecting stock vests by holding on till they hit their “number” for retirement.

How you handle this corporate ride depends on your personality archetype, which we will get into next.

The Three Corporate Engineer Archetypes

In all likelihood, your personality fits into one of three types:

The go-getter: You are Type A. You push hard to move up. You want the C-suite, and you will play the game to get there.

The worker: You have no problem getting the work done as long as the paychecks are nice. You find meaning outside of work. You play music, or coach kids’ football.

The nerd: In a non-derogatory sense, you truly enjoy doing technical things and solving hard problems. Learning gives you energy, and you want to do more of it, but you find it difficult to connect it to the limited scope of your job function.

As a go-getter, you have no problem being motivated at work and doing what it takes to get ahead. People with this mindset often find creative ways to get out of ruts by talking and networking their way through everything. I quite admire people like this actually — maybe because it does not come easily to me.

The worker is a good place to be, if you can swing it. A good paycheck and balanced life is possible if you decouple your identity from the technical work that you do, which is quite difficult for the high achieving brainiac types that often work in engineering. People like this understand that there is more to life than career and money — a holistic view that most often really works.

I personally fit the nerd category because of the incessant need to keep learning something new (hence this Substack). While companies say they encourage skill development, the skills you are excited to learn might not apply to your job description. So you’re left to your own devices to keep your intellect satisfied.

So let’s talk about nerds — just because it is the only archetype I can talk about.

The Case for Continuous Learning While Still Employed

To execute at a high level as a nerd archetype, it is important to frame the thinking right: learning is an atelic activity — something you do for the sake of doing. If that means you take courses in analog design, RF, signal processing, or even something entirely different like learning to program in Rust, you do it for the sake of learning. Why?

There is no guarantee that the skills you pick up will meaningfully transform your career. One possible scenario could look something like this.

You learn analog design through courses and textbooks.

You convince an employer to give you a job working on analog design.

You spend the next 5-7 years doing analog design till that feels like a rut.

In the best case, your skills take you interesting places you never could have imagined.

There is nothing wrong with doing something till that bores you, and then moving on. Prof. Gabriel Rebeiz, a UC San Diego professor I really admire for his work on phased arrays, said at a panel session in IMS 2025 that everyone needs to constantly reinvent themselves from time to time. He often tells his PhD students that if they are working in the same field as their PhD ten years from now, they’re doing it wrong. And there is no such thing as “too late” for a shift — most definitely not at the 7 year mark in a career like the reader asked.

Also, when you pick up surrounding skills outside your main line of expertise, it gives you a unique selling proposition for future job opportunities. How many people understand digital, analog and signal processing at a high level? This is something I discussed in detail in my last FAQ post.

I’ll end this discussion with a few strong reasons you should pursue learning adjacent domains while still employed at a big company.

You have access to industry standard tools, and know how to use them already: This is a big disadvantage for people who are not already in the semiconductor industry. But, if you have access to proprietary PDKs and state-of-the-art industry tools, nothing is stopping you from learning to design an operational transconductance amplifier (OTA) or bandgap reference circuit, if you’re interested in analog design.

You can learn from industry experts right across the hall: Most useful engineering skills are not written down in books, and comes only from experience. Luckily, even a reasonably sized company will have all sorts of experts you can learn from — and more often than not — they are happy to talk to you about their insights.

You have more financial resources at your disposal: A full time paycheck allows you to buy courses and learning materials, which can possibly even be reimbursed by the tuition assistance program at your company. What you lack in time, you can make up for in well organized learning resources, which helps you learn faster.

You can leverage internal opportunities at the company: It is often much easier to transition into a different role within the same company. You can reach out to the hiring manager directly, while keeping your current manager informed of your planned transition. You can even convince the new manager to allow you a short trial period on the job, with a few extra responsibilities, while you’re still in your original role. This is a much smoother way to move around in your career.

So, if you feel like you’re stuck in a rut doing the same tasks everyday, here are the three things you can evaluate for yourself:

Which phase of the Game of Life: MegaCorp edition are you in?

What is your engineer archetype?

If continuous learning is your thing, then ask what you can start learning today instead of trying to map the effort to future career outcomes.

The pieces will eventually fall into place. Good luck on your engineering adventures!

Wow. Vikram, this just opened flood gates in my mind. I’m at the 20+ year stage of semiconductor career and always felt like a misfit although I love the field of work. Thanks for sharing that people like me (the nerd archetype) do exist (in sizable numbers, I hope). I’ve always met about a handful of my types in every place I worked (out of 1000s of employees).

I’m not interested in mgmt positions or managing people. Always excited by technology, more complicated the better! My midlife crisis drove me to accrue more than avg knowledge in multiple domains, none of which are useful in my field of work, but helps me unwind and keep the excitement going in my life while I balance kids, fitness, finances and work.

This was a lovely read. The graph was quite interesting and undoubtedly pleasant to look at!